Infective endocarditis is the inflammation of the endocardium. It can affect the endocardium itself, the heart valves, and even intracardiac devices. It is a disease primarily caused by bacteria and presents with a wide range of manifestations. Without timely diagnosis and treatment, numerous intracardiac and extensive extracardiac complications can occur.

It is classified into acute and subacute forms. Acute endocarditis is a febrile illness that rapidly destroys cardiac structures and spreads hematogenously. It can be fatal within weeks if not treated. Subacute endocarditis follows a slower disease course and may remain active for weeks to months, with gradual progression.

Rationale

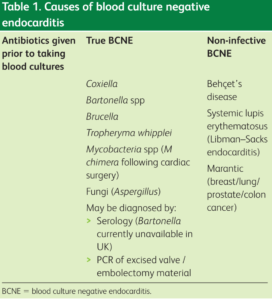

The overwhelming majority of infective endocarditis cases are caused by Gram-positive streptococci, staphylococci, and enterococci. Together, these three groups account for 80% to 90% of all cases, with Staphylococcus aureus specifically responsible for about 30% of cases in the developed world. In addition to various streptococcal species, other common colonizers of the oropharynx, such as the HACEK organisms (Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella), may also be responsible. Many other bacteria have been identified historically, but they account for only about 6% of all cases. Finally, fungal endocarditis represents only about 1% of cases but can be a fatal complication of typical systemic infections with Candida and Aspergillus species in immunocompromised populations.

Figure 1: Godfrey et al. Clin Med (Lond). 2020 Jul;20(4):412-416.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Infective endocarditis is a rare condition with an estimated annual incidence of 3 to 10 cases per 100,000 individuals. This disease has shown a preference for males, with a male-to-female ratio of nearly 2 to 1. The average age of patients with infective endocarditis is now over 65 years. This shift toward older patients likely reflects the prevalence of predisposing factors such as prosthetic valves, intracardiac devices, acquired valvular diseases, and diabetes mellitus. Although previously a major risk factor, rheumatic heart disease now accounts for less than 5% of all cases in the modern antibiotic era. Other factors that increase the risk include recent dental procedures, the presence of a permanent intravenous catheter, immunosuppression, and hemodialysis.

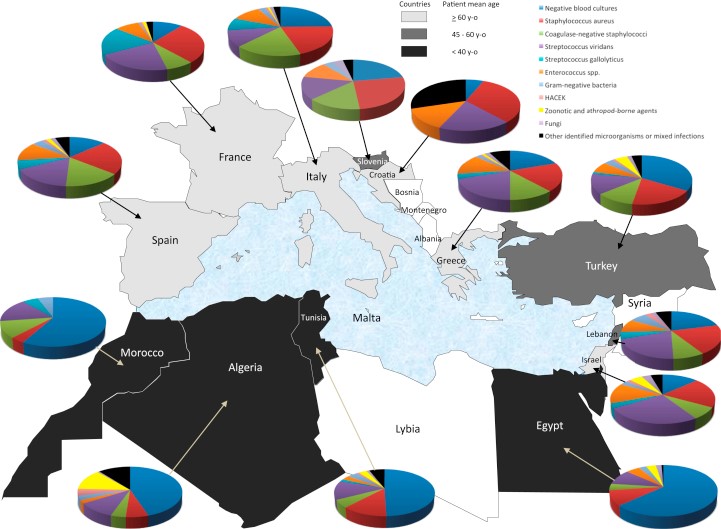

Image 2: Gouriet, F., et al., Endocarditis in the Mediterranean Basin. New Microbes New Infect, 2018. 26: p. S43-S51.

Symptoms

Clinically, infectious endocarditis can present with numerous symptoms, and clinicians should consider this diagnosis in any patient with increased risk factors who presents with fever or sepsis of unknown origin.

Fever (usually above 38°C) is the most common symptom, occurring in more than 95% of patients. It may be accompanied by chills, night sweats, and fatigue. However, factors such as immunosuppression, old age, use of antipyretics, or prior antibiotic treatment may prevent the manifestation of fever and reduce its frequency.

Other nonspecific symptoms indicative of systemic infection, such as anorexia, headache, loss of appetite, myalgias, generalized weakness, as well as cough, pleuritic chest pain, and arthralgias, may also be present. Symptoms helping to localize the infection to the cardiopulmonary system—such as chest pain, dyspnea, reduced exercise tolerance, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea—occur less frequently and should raise concern for underlying aortic or mitral valve insufficiency. In cases of acute valvular insufficiency, patients may experience sudden symptoms of heart failure.

Cardiac murmurs are observed in about 85% of patients. Congestive heart failure develops in 30% to 40% of patients, usually due to valvular dysfunction. Cutaneous manifestations may include petechiae or splinter hemorrhages. Osler's nodes (painful subcutaneous nodules typically found on the palms), Roth spots, subungual hemorrhages, and Janeway lesions (painless hemorrhagic plaques on the palms/soles) are observed in fewer than 10% of cases.

Possible complications of endocarditis include cardiac conduction abnormalities (such as first-degree atrioventricular block, bundle branch block, or complete heart block), ischemia (due to coronary artery emboli), embolic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, brain abscess, and septic emboli leading to infarction of the kidneys, spleen, lungs, and other organs.

| Research | Loupa et al. | Giannitsioti et al. |

| Patients | ||

| Number | 101 | 195 |

| Median age | 54.4 | 63.3 |

| Male/Female | 71/30 (2.4) | 126/69 (1.8) |

| Time period | 1997-2000 | 2000-2004 |

| Number of research centers | 1 | 20 |

| Rheumatic heart disease (%) | 7 (6.9) | 28 (14.3) |

| Prosthetic valve (%) | 31 (30.7) | 42 (21.5) |

| Pacemaker (%) | 11 (10.9) | na |

| Surgery (%) | 52 (51.5) | 53 (27.2) |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 16 (15.8) | 39 (20.0) |

| Microorganisms | ||

| Negative blood cultures (%) | 22 (21.8) | 37 (18.9) |

| Staphylococcus aureus (%) | 22 (21.8) | 34 (17.4) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci (%) | 16 (15.8) | 19 (9.7) |

| Streptococcus viridans (%) | 19 (18.8) | 40 (20.5) |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus (%) | 1 (0.9) | 9 (4.6) |

| Enterococcus spp. (%) | 3 (2.9) | 38 (37.6) |

| Non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria (%) | 3 (2.9) | 0 |

| Enterobacteriaceae (%) | 3 (2.9) | 0 |

| HACEK (%) | 2 (1.9) | 0 |

| Brucella spp. (%) | 2 (1.9) | 0 |

| Bartonella spp. (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Coxiella burnetii (%) | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Fungus (%) | 6 (5.9) | 0 |

| Other microorganisms or mixed infections (%) | 5 (4.9) | 18 (9.2) |

Blood cultures

At least three sets of blood cultures should be taken from different venipuncture sites, which should be separated by at least 1 hour, before the initiation of antibiotic therapy. If the cultures remain negative after 48 to 72 hours, two or three additional sets should be taken.

Blood culture-negative endocarditis is defined as endocarditis with no definitive microbiological etiology after at least three independently obtained blood cultures. Up to 14% of patients may have negative blood cultures due to prior antibiotic therapy or due to organisms such as Coxiella, Legionella, Bartonella, Mycoplasma, Brucella, Chlamydia, and fungi.

Molecular Syndromic Diagnosis of Endocarditis in valve/heart tissue or blood is performed in the Diagnostic Department of the Infectious Disease Institute.

| Bartonella sp. |

| Tropheryma whipplei |

| Coxiella burnetti |

| Escherichia coli |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

| Enteroccocus faecium |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus (bovis) |

| Streptococcι στοματικής κοιλότητας (S. mitis, S. sanguinis, S. salivarius, S. mutans, S. gordonii, S. oralis) |

| 16S rRNA (standard PCR και sequencing) |